Technological advances can have a variety of effects on access to information. New technologies can change the breadth, depth, and sheer amount of information we can readily consume. They can also fundamentally change the way in which we organize and access that information. One example is the way in which the use geolocation coordinates (also knows as GIS data) as an access tool has changed in the last decade or so.

While I was working at the Avery Library of Architectural and Fine Arts I was part of a concerted effort to explore the possibilities that GIS data offers for providing access to and context for collections. This is a brief look at three different projects that highlight different ways in which the same basic data can be used to change the way in which a library user interacts with a collection.

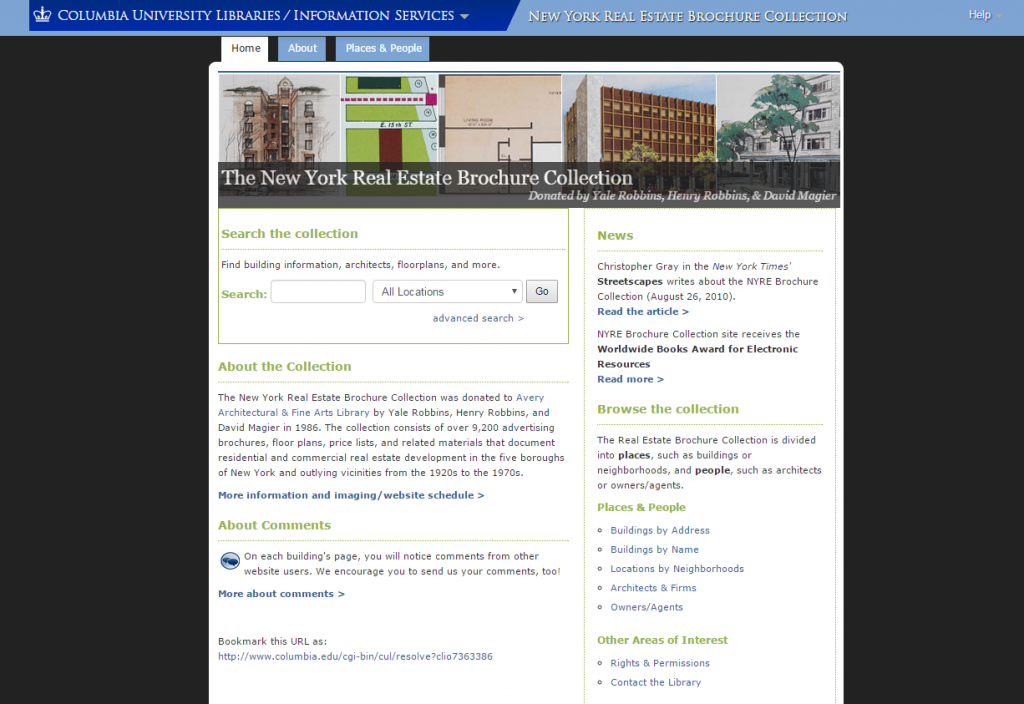

The New York Real Estate Brochures (NYRE) Collection

The NYRE project is a look at a collection of over 9,200 individual pieces of real estate promotional materials from the greater NYC area, starting in the 1920s and ending in the 1970s. It was launched in 2010 and is a valuable resource for researchers interested in trends in NYC real estate development, and the first project at Avery to include geolocation as an active component of the discovery process.

The collection consists of over 9,200 advertising brochures, floor plans, price lists, and related materials that document residential and commercial real estate development in the five boroughs of New York and outlying vicinities from the 1920s to the 1970s.

For this project, GIS coordinate information was added to the bibliographic record and then used to tag each object as being part of a neighborhood. Researchers then have the option to filter the collection by neighborhood, and the interface plots all of the materials tagged to a particular neighborhood on a map. The data is being used to section the collection into areas of potential research interest, and then to show how items of a specific designation interact geographically with one another.

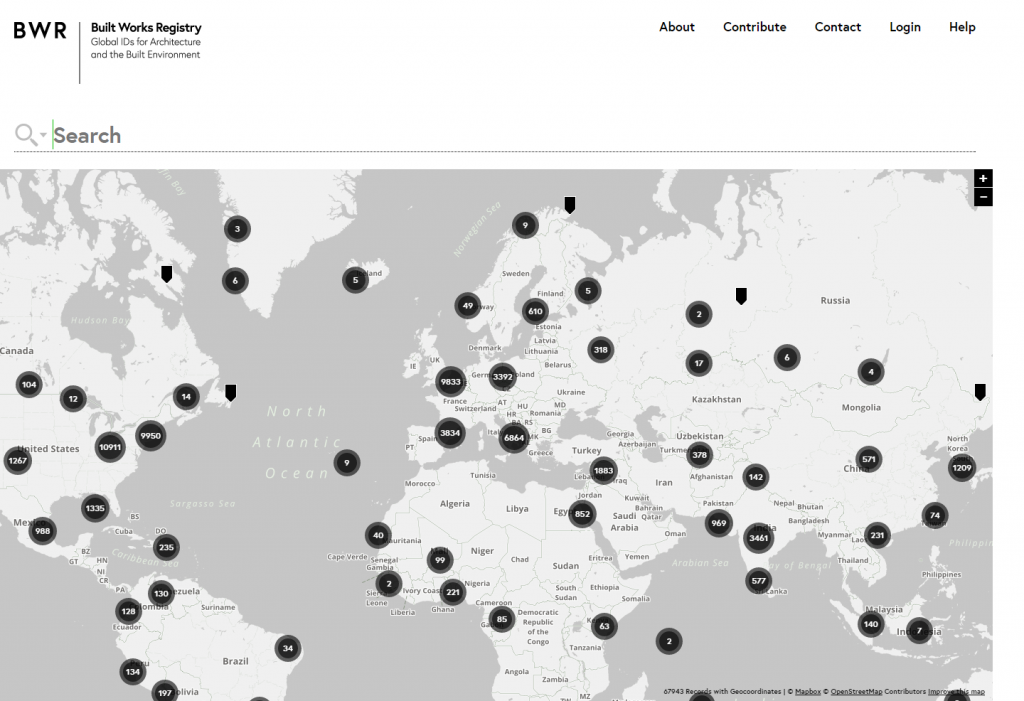

Built Works Registry

The Built Works Registry was launched in 2014 as an attempt to create a geolocation authority control resource for works of architecture around the world. The project brings together data from forty-two different sources to form a single data entity that provides a point of reference for a building’s geographical location, similar to the function provides by the ISBN/ISSN standards. If you are interested in learning more about how the project came together feel free to check out the project blog.

Wy is this resource important? Building names and associations can and do change (for example, did you know that the New York Waldorf Astoria Hotel changed locations in the late 1920s?). I was briefly involved in the data validation effort for this project, and I can tell you from first hand experience that identifying a structure from its name or other descriptive information can be a difficult task. However, including the BWR identifier in your dataset lets users know exactly what building is being described.

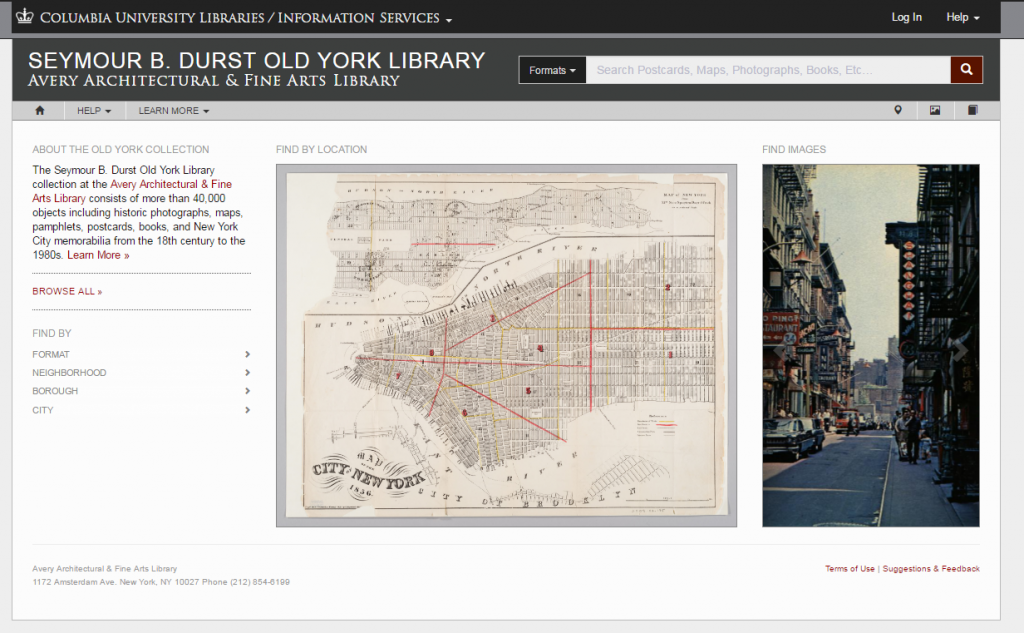

Seymour B. Durst Old York Library

The Old York Library project was what I worked on for most of my tenure at Avery, a collection of over 40,000 objects related in one way or another to New York City. Collection materials span over 200 years (from the late 16th century into the late 20th), and cover a variety of topics and subject matter, including politics, economics, art, special events, and real estate development and the built environment. The only thread joining all of these items together is their relationship to NYC.

Because the collection focus was geographic in nature, we decided to include geographic information (neighborhood, street address, GIS coordinates) about an item’s subject matter, and to use that data to develop a map-based discovery tool, giving users of the site a spatial discovery tool to go along with more traditional text-based searches. This approach puts special emphasis on where something took place, and gives users an intuitive, “physical” interface to relate that something to other collection materials based on their location.

The main lesson I learned while working on these projects was about the versatility of tools. All of these projects basically use the same GIS data; what varies is the purpose to which the data is put, based on the different perceived needs of each project’s target audience. There is no single way of providing access to a collection, just a set of tools that librarians can use in whatever way they believe best fits the user’s information needs.